The

Fascination of Japanese

lacquer Inro and Boxes

A personal view by

John Neville Cohen

(as written for publication in 1995)

Japanese lacquer inro and boxes are such incredibly beautiful works of art, particularly, pieces from the late 18th and early 19th century.

I consider many of them to rate very highly, amongst the finest treasures of the World!

Without I hope being too technical, my intention is to use and to explain the terms and names, that are most commonly in use. This way readers who might be tempted to look at sale catalogues, will be more able to appreciate and understand the descriptions.

Inro Fashion

With the introduction of the kimono, the 'Inro' became one of the most important and essential fashion accessories used to carry on ones person such items as ink seals and medicines.

The Kimono had no pockets so the inro was a clever container, consisting of a number of interlocking small separate sections, all held together on a silk cord and worn hanging from the sash tied at the waist. Soon it evolved from a purely functional item to one of very high fashion, and the designs and decoration gradually became richer, finer and even more lavish.

Netsuke and Ojime

A bead known as an 'Ojime' kept the various sections closed tight together.

A toggle normally a small wood or ivory carving known as a 'Netsuke' would also be threaded on to the silk cord.

The netsuke (these are such superb little sculptures) would be pushed up under the sash

(known as the

'Obi') that was tied round the waist, and would thus hold the inro hanging below.

The silk cord would have had to be about 56 inches long, and was threaded in such a way, that about 3 to 4 inches of the cord would show below the

'Obi' to the 'Ojime' and inro.

Are you still with me? Under the inro a many-looped special bow was formed, with normally six loops all of the same size. There would only be one knot and this would be hidden in the larger of the two cord holes, within the

netsuke.

No loose ends would be visible.

Sometimes a 'Manju' would be used instead of the netsuke. These are rather like a thick pocket watch shaped carving, comprising two sections that open up.

The lower piece has a central hole, and an eyelet for the cord is fixed inside the upper section.

Once attached to the cord, the knot would remain hidden inside but unlike the

netsuke, the carving or decoration of a manju is only two-dimensional.

The earliest 'Ojime' were simply a drilled bead, often of coral, as they had faith in a superstition that coral would disintegrate if near to poison. Quite valuable to them, if only it had been true, as they carried and took some very strange medicines.

Later semiprecious stones and ivory were used, some of them are beautifully carved, and there are also many very fine metal

ojime.

Today collectors even specialise in just ojime and they have become quite valuable.

I do think it is rather a shame that so many of these items are now collected separately, when they really all belong together.

For many years there have been netsuke collectors, and I can appreciate why, as they are complete artworks, as well as being wonderful handling pieces.

Anyway, so many netsuke collectors given time find they are tempted by

inro too!

I always considered myself to be rather a specialist collector, but I would not be happy to own

inro, without ojime or netsuke, as they would seem so incomplete! I could not imagine being satisfied with only collecting the ojime, beautiful as some of them are.

Obviously, these high prices have been the main reason for such specialisation!

Keeping Lacquer

Great care needs to be taken when handling lacquer, as it can so easily be damaged by knocks.

The most common cause occurs when the inro is picked up, for if the

netsuke is allowed to swing and bump into the inro, the lacquer will dent and chip.

One should always try to hold the silk cord when inspecting inro, rather than finger the

lacquer, as there is something in our perspiration that dulls the shine in time.

All lacquer is best kept in a reasonably humid atmosphere avoiding sudden changes of temperature. This is not so difficult to arrange in this country, it is simply a matter of keeping a bowl of water in the same cabinet and avoiding the use of any hot spot lights.

Lacquer Boxes

Most of the early boxes were made to keep things in, such as 'Suzuribako', these were fully fitted writing boxes that contained the ink block, water dropper, all the brushes and tools.

Some were fitted with all the requirements for pastimes such as the 'Incense Game' or the

'Shell Game', whilst others were designed as picnic sets.

A lot of lacquer boxes were used as a means of packaging, for deliveries of documents, or sweet cakes and gifts.

The practice used to be that once filled with gifts, they were then simply wrapped in a material that was formed into a sack.

This was then carried, over the shoulder, by the messenger and delivered.

The recipient would later have all the boxes returned, normally with a note and something little in them, as a gift to say thank you, and so these

boxes would be used over and over again.

They all are beautifully decorated and it is surprising to us that these

boxes were not, in those days, considered more valuable.

The Designs

Nearly all the designs were taken from early classical literature, paintings or woodblocks.

Printed picture books had become very popular in the 17th century.

They hardly ever had any text, but many of the illustrations were copied and used by

lacquer artists, in the same way as other craftsmen had done, such as enamellers, potters and metal workers.

This is why we find various popular scenes recurring in inro, such as the young herdsman playing the flute next to his resting ox, and

'Rosei's dream' is another subject frequently found.

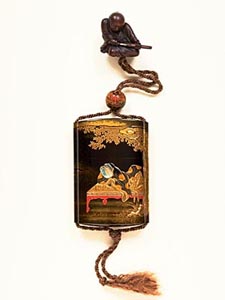

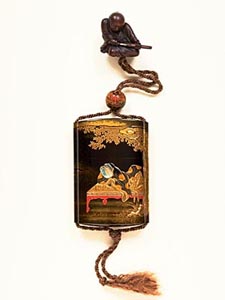

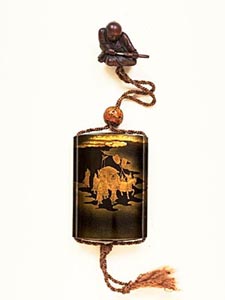

The photograph of an inro depicting Rosei's dream is a very fine example: it shows him partially hidden by his fan that is inlaid with a very thin piece of iridescent shell.

At certain angles of light his face can clearly be seen. On the reverse, in superbly fine gold work, is the subject of his dream. He is dreaming of his ride in a stately court procession.

This inro is Signed Komo Kyuhaku.

Together with this inro is a lacquer ojime, and a wood netsuke, carved as a kneeling man with a dagger. This intriguing netsuke is signed Minko. By pulling gently on the sheath, the steel blade comes into view, creating quite an illusion.

I must apologise, as the silk cord is not tied in the correct fashion in both of the

inro photographed - one day I shall have to put this right!

Compositions in general favoured nature, animals, flowers, birds, insects, Mount Fuji, every day life, myths and legends. The first western visitors also fascinated the Japanese. The Portuguese were the first to arrive in 1542, followed soon by the Dutch, and all the arts were greatly influenced from the mid 16th century onwards. Dutchmen in particular are featured quite frequently in a wide range of

Asian art.

Amazing Skills

Many of the new Japanese techniques and most of the superb designs were originally to be found on the 14th and 15th century Boxes. The skills and control in decoration that were developed in the 18th and early 19th century, were based both on these earlier techniques and designs, but this was a period where new peaks were reached and breathtakingly beautiful

lacquer works have been created.

Several craftsmen were involved in the making of an inro. First the very thin wood base would have been painstakingly made, with carefully selected wood, where all the knots had to be avoided. Conifers were preferred as this wood contained very little resin.

It would then have been handed to the next craftsman, a specialist at applying the numerous base layers of lacquer. Each layer would be extremely thin, and gradually finer and finer quality

lacquer was used, at least 30 layers were applied, so that no trace of the wood inside could any longer be visible. Only at this stage would the lacquer artist responsible to design and create the many layers of decoration begin.

What does seem amazing to me, when one considers how the wood base was made, was the fact that they would have had to make allowances for the thickness of all these layers. Yet the Inro sections fit and slot into each other so perfectly, that one can hardly see any of the dividing lines once closed.

The Decoration

Often two artists would collaborate to decorate an inro, one a lacquer artist, the other could be a metal worker or even a

netsuke carver, providing wonderfully worked items, that would be inlaid in the

lacquer. Various materials have been used in this way such as precious metals,

pottery, ivory, shell, horn and many others. Incidentally, there had to be very close collaboration, for each time an inlay in the design overlapped more than one section, it had to be made in two pieces to allow the

inro to open. Such inro often have two signatures as both of the artists would sign.

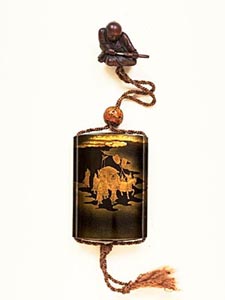

The superb gold inro photographed is decorated with exquisitely applied metal work, the scene being of an outside stage with two actors. One is an archer, about to fire his bow at the other on the reverse, who is crouching down protecting a monkey.

The face of the archer, although mostly viewed in profile, surprisingly, has his full-face details if viewed from the side.

The remarkable metal work extends over three of the inro sections. In this particular case, both the

lacquer and the metal work were by the same artist and it is signed Noriyuki.

This inro has an attractive metal ojime, and a good ivory netsuke, of two musicians. The netsuke is signed Harumin.

The Artists

Signatures however, are not always a sure way of knowing who did the work. Often the signature was placed in honour, not as a forgery, of a great artist who originated the design such as the top early artists Ritsuo and Korin. Many very fine lacquer works were not signed at all. Pieces that were commissioned by the Shogun or Daimyo, where only the highest of standards were acceptable, would not normally be signed, no matter how important the artist.

In 1868 the Meiji restoration meant the loss of such patrons, and Japan had opened up to the west. This meant that artists had to try to appeal to new clients, with an unknown western taste. Thank goodness, they were not prepared however, to give up certain of their traditional designs and techniques.

Family names passed down from one generation to another; the name of a particularly admired artist would be signed by all the following generations. They would also have non related students, who would be encouraged to use the same name, on work of a high enough standard, that is, until they were sufficiently proficient to become independent. One such family name was Koma, where the later very famous 19th century artist, Shibata Zeshin was taught.

There is a wonderful display of inro by Zeshin at the V & A Museum, of a collection based on the twelve months of the year, which is well worth a visit. Each piece is superb, and a large variety of techniques can be seen all in one place!

The Great Schools

The finest artists were all talented members of schools, often under the supervision of a master, such as Koma and Kajikawa, and these two schools produced high quality

lacquer for over two hundred years. Other schools have become known for their special techniques. One is Somada that specialised in very fine

shell inlay; another is Shibayama who worked with more thickly encrusted materials such as

shell, ivory, soapstone, pottery and many other materials. There was also Tsuishu Yosei who brilliantly carved red Lacquer, but the Shiomi Masanari School favoured the most difficult technique of all, known as

'Togadashi' where the surface is kept perfectly flat.

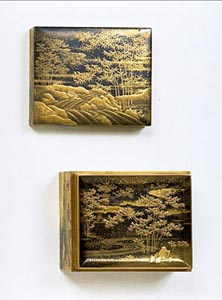

Superb quality lacquer work was not restricted to inro, but there are also some magnificent boxes that were used, such as

'Bunko' for documents, 'Fubako' for letters and 'Kogo' incense boxes, originally used for cosmetics. Some of these boxes also have a fitted tray, and sometimes a set of smaller boxes, that all fit perfectly inside. Many of these items including the already described writing, games and picnic boxes as well as pieces of furniture, can all be found just as finely decorated as

inro.

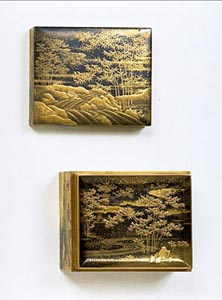

The little kogo photographed is signed Kosentie and so beautifully decorated on the cover and sides, with continuous scenes of bamboo growing besides a running stream. The fitted tray has a similar scene and every other part is covered in tiny gold pieces, each placed by hand individually. So much richer a finish is achieved, than the more usual 'Nashiji', where fine gold is carefully sprinkled on!

If you have a good eye for composition the appreciation of lacquer work is hard to resist. On inro they have very ingenious methods of design to make one wish to see the other side, such as the use of a rope that mysteriously disappears round the side, or a scroll that flows round the

inro.

When we began collecting, we were simply only buying pieces that we instinctively liked, and we have had no regrets. There is so much to learn however, once one becomes interested, especially these days when modern inro are being produced to a very high standard. Having seen the work of Unryuan, a very good artist born in 1952, his

modern inro command nearly as much as the earlier works. So many inro these days have been very cleverly repaired and now that so much money is involved a lot of care when buying is needed.

I do hope that there will always be private collections and that lacquer will not be confined to Museums, as it is such a fascinating hobby!

John Neville Cohen, is a multifaceted photographic artist and collector, who defies categorization.

His creative endeavours span projection photography, where he

masterfully blends light and form, creating International award

winning photographs, to his passion for collecting Asian antiques

and classic Jensen cars. Additionally, he has contributed

interesting articles, and published 'The History of Jacey Cinemas',

a unique stamp collecting album for little people, apart from 'The

Trudy and John Neville Cohen Collection' of antiques. Have a look at

his 'Homepage' https://www.jncohen.net

To see other articles, with

photographs, please use the following link:

https://www.jncohen.com/_antiques/Articles/articles.htm

|